Procopius Waldvogel

Procopius Waldvogel (alternative spellings: Prokop Waldvogel or Procopius Waldfogel) was a medieval printer based in Avignon. It is believed by some that he might have invented printing before Johannes Gutenberg, although Waldvogel likely learned printing via Gutenberg.[1] Waldvogel lived in the 15th century.

Life

[edit]Waldvogel was a German living in Avignon, and was a silversmith by trade.[2] He fled from Prague during the Hussite troubles and stayed in Lucerne, Switzerland.[3] He moved to Avignon in 1444.[4] In Avignon he had two students: Manaud Vitalis and Arnaud de Coselhac.[5][6] Waldvogel's name appears in several contracts of that time, most notably the one in which he agrees to provide Davin de Caderousse with equipment for reproducing Hebrew texts.[7] Waldvogel disappeared from the historical records after 1446.[8]

Career

[edit]It has been claimed by some that he owned molds for printing in 1444, before Johannes Gutenberg. However, unlike Gutenberg, he did not print any books, and Gutenberg had his printing press probably already finished by 1440.[9]

Waldvogel offered to teach the art of artificial writing to a schoolteacher.[10][vague]

In 1890, the French historian M. Requin claimed that Waldvogel had invented the art of moveable type printing before Johannes Gutenberg. However, Requin never showed any evidence that Waldvogel printed anything, and his allegations are long forgotten.[11][12]

He was a contemporary of other alleged printers of the time, which included Laurens Janszoon Coster, Jean Brito and Panfilo Castaldi.[13][14]

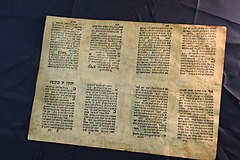

Controversial printed quires possibly assigned to Procopius Waldvogel

[edit]

In 2015, two Hebrew-letter quires with a total of 32 pages were found to be reused in the cover of a book from the 16th century. They were sent by their owner to the Institute of Hebrew Manuscript Research at the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem. The study of their watermarks, paper, ink, typeset typography, made upon request of their owner, concluded that it may be possible that they could have been printed in the area of Avignon around 1444, suggesting that they might be Waldvogel and Davin de Caderousse's work. This finding has received some media coverage, although in the absence of a counter-expertise by independent scholars, the putative link between these printed quires and Waldfogel's entreprise remains purely speculative.

Since 2019, the Institute for Computerized Bibliography of the Hebrew Book published three studies on the sheets, which were brought in 2015 before Yitzhak Yudlov, who was the Head of the Institute for Hebrew Bibliography in Jerusalem for many years, and Benjamin Richler, former Director of the Institute of Microfilmed Hebrew Manuscripts at the National Library in Jerusalem. Regarding the identification of those sheets, they wrote: "In our opinion, these are the sheets from the printing experiments of Prokop Waldvogel and Davin from Caderousse".

The publications of the Institute for Computerized Bibliography of the Hebrew Book dealt with three components of the sheets, namely paper, watermark and typography.

References

[edit]- ^ Freivogel, Thomas (7 August 2013). "Procopius Waldvogel". Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in French).

- ^ "The mystery of Procopius Waldvogel". europeanhistory.about.com. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ Der Geschichtsfreund: Mitteilungen des Historischen Vereins Zentralschweiz, Vol. 84 Buchdruckerlexikon,Teil I. Luzern: Fritz Blaser. 1929. p. 167.

- ^ Man, J. (2010). The Gutenberg Revolution. Transworld. p. 118. ISBN 9781409045526. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ "Page:Popular Science Monthly Volume 38.djvu/880 - Wikisource, the free online library". en.wikisource.org. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ "p.182-3. The American Journal of Archæology: And of the History of the Fine Arts; 1891". forgottenbooks.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 2015-11-16.

- ^ Febvre, L.; Martin, H.J. (1976). The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing 1450-1800. Verso. p. 52. ISBN 9781859841082. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ Childress, D. (2008). Johannes Gutenberg and the Printing Press. Ebsco Publishing. p. 147. ISBN 9780761340249. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ "Printing and Publishing - Renaissance: An Encyclopedia for Students | Encyclopedia.com". encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ Fellow, A. (2009). American Media History. Cengage Learning. p. 3. ISBN 9781111781552. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ "Sacramento Daily Union 27 September 1890 — California Digital Newspaper Collection". cdnc.ucr.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ (In French) ספרו של האב The Origins of Printing in France - P. Requin, Origines de l'imprimerie en France, 1891. (Google Books). Requin's discovery was known to researchers through Cecil Roth's book 1957 Jews in the Renaissance pages 167-8 (Online book at the Jerusalem National Library of Israel)

- ^ School of Library and Information Sciences University of North Carolina Frederick G. Kilgour Distinguished Research Professor, C.H. (1998). The Evolution of the Book. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 85. ISBN 9780195353365. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- ^ McGrath, Alister E. (12 April 2012). In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible. ISBN 9781444745269.

External links

[edit]- "Waldvogel, Prokop". ADB:Waldvogel, Prokop – Wikisource. Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie. de.wikisource.org. 1896. p. 725. Retrieved 2014-10-05.

- "Prokop <Waldvogel>". thesaurus.cerl.org. Retrieved 2014-10-05.