2020 Atlantic hurricane season

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (September 2024) |

| 2020 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 16, 2020 |

| Last system dissipated | November 18, 2020 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Iota |

| • Maximum winds | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 917 mbar (hPa; 27.08 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 31 (record high, tied with 2005) |

| Total storms | 30 (record high) |

| Hurricanes | 14 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 7 (record high, tied with 2005) |

| Total fatalities | 432 total |

| Total damage | > $55.394 billion (2020 USD) |

| Related articles | |

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season is the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record, in terms of number of systems. It featured a total of 31 tropical or subtropical cyclones, with all but one cyclone becoming a named storm. Of the 30 named storms, 14 developed into hurricanes, and a record-tying seven further intensified into major hurricanes.[nb 1] It was the second and final season to use the Greek letter storm naming system, the first being 2005, the previous record. Of the 30 named storms, 11 of them made landfall in the contiguous United States, breaking the record of nine set in 1916. During the season, 27 tropical storms established a new record for earliest formation date by storm number.[nb 2] This season also featured a record ten tropical cyclones that underwent rapid intensification, tying it with 1995, as well as tying the record for most Category 4 hurricanes in a singular season in the Atlantic Basin. This unprecedented activity was fueled by a La Niña that developed in the summer months of 2020, continuing a stretch of above-average seasonal activity that began in 2016. Despite the record-high activity, this was the first season since 2015 in which no Category 5 hurricanes formed.[nb 3]

The season officially started on June 1 and officially ended on November 30. However, tropical cyclogenesis is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated by the early formation of Tropical Storms Arthur and Bertha, on May 16 and 27, respectively. This was the sixth consecutive year with a pre-season system and the second of these seasons to have two, with the other being 2016.[4] The first hurricane, Hurricane Hanna, made landfall in Texas on July 25. Hurricane Isaias formed on July 31, and made landfall in The Bahamas and North Carolina in early August, both times as a Category 1 hurricane; Isaias caused $4.8 billion in damage overall.[nb 4] In late August, Laura made landfall in Louisiana as a Category 4 hurricane, becoming the strongest tropical cyclone on record in terms of wind speed to make landfall in the state, alongside the 1856 Last Island hurricane and Ida. Laura caused at least $19 billion in damage and 77 deaths. September was the most active month on record in the Atlantic, with ten named storms. Slow-moving Hurricane Sally impacted the United States Gulf Coast, causing severe flooding. The Greek alphabet was used for only the second and final time, starting on September 17 with Subtropical Storm Alpha, which made landfall in Portugal on the following day.

Hurricane Zeta struck Louisiana on October 28, becoming the fourth named storm of the season to make landfall in the state, tying the record set in 2002. Zeta also struck the United States later in the calendar year than any major hurricane on record. On the last day of October, Hurricane Eta formed and made landfall in Nicaragua at Category 4 strength on November 3. Eta ultimately led to the deaths of at least 175 people and caused $8.3 billion in damage. Then, on November 10, Tropical Storm Theta became the record-breaking 29th named storm of the season and, three days later, Hurricane Iota formed in the Caribbean. Iota rapidly intensified into a high-end Category 4 hurricane, which also made 2020 the only recorded season with two major hurricanes in November. Iota ultimately made landfall in the same general area of Nicaragua that Eta had just weeks earlier and caused catastrophic damage. Overall, the tropical cyclones of the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season collectively caused at least 432 deaths and over $55.4 billion in damage, totaling to the seventh costliest season on record.

All forecasting agencies predicted above-average activity, some well-above-average, citing factors such as the expectation of low wind shear, abnormally warm sea surface temperatures, and a neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation or La Niña. Climate change likely played a role in the record-breaking season, with respect to intensity and rainfall. However, each prediction, even those issued during the season, underestimated the actual amount of activity. Early in 2020, officials in the United States expressed concerns the hurricane season could exacerbate the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic for coastal residents due to the potential for a breakdown of safety protocols such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders.

Seasonal forecasts

[edit]| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

Ref |

| Average (1981–2010) | 12.1 | 6.4 | 2.7 | [1] | |

| Record high activity | 30‡ | 15 | 7† | [5] | |

| Record low activity | 1 | 0† | 0† | [5] | |

| TSR | December 19, 2019 | 15 | 7 | 4 | [6] |

| CSU | April 2, 2020 | 16 | 8 | 4 | [7] |

| TSR | April 7, 2020 | 16 | 8 | 3 | [8] |

| UA | April 13, 2020 | 19 | 10 | 5 | [9] |

| TWC | April 15, 2020 | 18 | 9 | 4 | [10] |

| NCSU | April 17, 2020 | 18–22 | 8–11 | 3–5 | [11] |

| PSU | April 21, 2020 | 15–24 | n/a | n/a | [12] |

| SMN | May 20, 2020 | 15–19 | 7–9 | 3–4 | [13] |

| UKMO* | May 20, 2020 | 13* | 7* | 3* | [14] |

| NOAA | May 21, 2020 | 13–19 | 6–10 | 3–6 | [15] |

| TSR | May 28, 2020 | 17 | 8 | 3 | [16] |

| CSU | June 4, 2020 | 19 | 9 | 4 | [17] |

| UA | June 12, 2020 | 17 | 11 | 4 | [18] |

| CSU | July 7, 2020 | 20 | 9 | 4 | [19] |

| TSR | July 7, 2020 | 18 | 8 | 4 | [20] |

| TWC | July 16, 2020 | 20 | 8 | 4 | [21] |

| CSU | August 5, 2020 | 24 | 12 | 5 | [22] |

| TSR | August 5, 2020 | 24 | 10 | 4 | [23] |

| NOAA | August 6, 2020 | 19–25 | 7–11 | 3–6 | [24] |

| Actual activity |

30 | 14 | 7 | ||

| * June–November only ‡ New record for activity † Most recent of several such occurrences (See all) | |||||

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts, such as Philip J. Klotzbach and his associates at Colorado State University (CSU), and separately by NOAA forecasters. Klotzbach's team (formerly led by William M. Gray) defined the average (1981 to 2010) hurricane season as featuring 12.1 tropical storms, 6.4 hurricanes, 2.7 major hurricanes (storms reaching at least Category 3 strength in the Saffir–Simpson scale), and an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index of 106 units.[7] Broadly speaking, ACE is a measure of the power of a tropical or subtropical storm multiplied by the length of time it existed. It is only calculated for full advisories on specific tropical and subtropical systems reaching or exceeding wind speeds of 39 mph (63 km/h). NOAA defines a season as above normal, near normal or below normal by a combination of the number of named storms, the number reaching hurricane strength, the number reaching major hurricane strength, and the ACE Index.[1]

Pre-season forecasts

[edit]On December 19, 2019, Tropical Storm Risk (TSR), a public consortium consisting of experts on insurance, risk management, and seasonal climate forecasting at University College London, issued an extended-range forecast predicting a slightly above-average hurricane season. In its report, the organization called for 15 named storms, 7 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 105 units. This forecast was based on the prediction of near-average trade winds and slightly warmer than normal sea surface temperatures across the tropical Atlantic as well as a neutral El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phase in the equatorial Pacific.[6] On April 2, 2020, forecasters at CSU echoed predictions of an above-average season, forecasting 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 4 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 150 units. The organization posted significantly heightened probabilities for hurricanes tracking through the Caribbean and hurricanes striking the U.S. coastline.[7] TSR updated their forecast on April 7, predicting 16 named storms, 8 hurricanes, 3 major hurricanes, and an ACE index of 130 units.[8] On April 13, the University of Arizona (UA) predicted a potentially hyperactive hurricane season: 19 named storms, 10 hurricanes, 5 major hurricanes, and accumulated cyclone energy index of 163 units.[9] A similar prediction of 18 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes was released by The Weather Company on April 15.[10] Following that, North Carolina State University released a similar forecast on April 17, also calling for a possibly hyperactive season with 18–22 named storms, 8–11 hurricanes and 3–5 major hurricanes.[11] On April 21, the Pennsylvania State University Earth Science System Center also predicted high numbers, 19.8 +/- 4.4 total named storms, range 15–24, best estimate 20.[12]

On May 20, Mexico's Servicio Meteorológico Nacional released their forecast for an above-average season with 15–19 named storms, 7–9 hurricanes, and 3–4 major hurricanes.[13] The UK Met Office released their outlook that same day, predicting average activity with 13 tropical storms, 7 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes expected to develop between June and November 2020. They also predicted an ACE index of around 110 units.[14] NOAA issued their forecast on May 21, calling for a 60% chance of an above-normal season with 13–19 named storms, 6–10 hurricanes, 3–6 major hurricanes, and an ACE index between 110% and 190% of the median. They cited the ongoing warm phase of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and the expectation of continued ENSO-neutral or even La Niña conditions during the peak of the season as factors that would increase activity.[15] TSR revised their forecast downward slightly on May 28, this time predicting 17 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 3 major hurricanes, while increasing the projected ACE index to 135.[16]

Mid-season forecasts

[edit]CSU released an updated forecast on June 4, calling for 19 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[17] UA issued their second prediction for the season on June 12, decreasing their numbers to 17 named storms, 11 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[18] On July 7, CSU released another updated forecast, predicting 20 named storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[19] That same day, TSR revised their forecast to 18 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[20] On July 16, The Weather Company released an updated forecast, calling for 20 named storms, 8 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.[21]

On August 5, CSU released an additional updated forecast, their final for 2020, calling for a near-record-breaking season, predicting a total of 24 named storms, 12 hurricanes, and 5 major hurricanes, citing the anomalously low wind shear and surface pressures across the basin during the month of July and substantially warmer than average tropical Atlantic and developing La Niña conditions.[25] On August 5, TSR released an updated forecast, their final for 2020, also calling for a near-record-breaking season, predicting a total of 24 named storms, 10 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes, citing the favorable July trade winds, low wind shear, warmer than average tropical Atlantic, and the anticipated La Niña.[26] The following day, NOAA released their second forecast for the season, in which they called for an "extremely active" season, predicting it would contain 19–25 named storms, 7–11 hurricanes, and 3–6 major hurricanes. This was one of the most active forecasts ever released by NOAA for an Atlantic hurricane season.[24]

Seasonal summary

[edit]

| 2020 tropical / subtropical storm formation records | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storm number |

New record | Old record | ||

| Name | Date formed | Name | Date formed | |

| 3 | Cristobal | June 2, 2020 | Colin | June 5, 2016 |

| 5 | Edouard * | July 6, 2020 | Emily | July 11, 2005 |

| 6 | Fay | July 9, 2020 | Franklin | July 21, 2005 |

| 7 | Gonzalo | July 22, 2020 | Gert | July 24, 2005 |

| 8 | Hanna | July 24, 2020 | Harvey | August 3, 2005 |

| 9 | Isaias | July 30, 2020 | Irene | August 7, 2005 |

| 10 | Josephine | August 13, 2020 | Jose | August 22, 2005 |

| 11 | Kyle | August 14, 2020 | Katrina | August 24, 2005 |

| 12 | Laura | August 21, 2020 | Luis | August 29, 1995 |

| 13 | Marco | August 22, 2020 | Maria | September 2, 2005 |

| Lee | September 2, 2011 | |||

| 14 | Nana | September 1, 2020 | Nate | September 5, 2005 |

| 15 | Omar | September 1, 2020 | Ophelia | September 7, 2005 |

| 16 | Paulette | September 7, 2020 | Philippe | September 17, 2005 |

| 17 | Rene | September 7, 2020 | Rita | September 18, 2005 |

| 18 | Sally | September 12, 2020 | Stan | October 2, 2005 |

| 19 | Teddy | September 14, 2020 | "Azores" | October 4, 2005 |

| 20 | Vicky | September 14, 2020 | Tammy | October 5, 2005 |

| 21 | Alpha | September 17, 2020 | Vince | October 8, 2005 |

| 22 | Wilfred | September 17, 2020 | Wilma | October 17, 2005 |

| 23 | Beta | September 18, 2020 | Alpha | October 22, 2005 |

| 24 | Gamma | October 2, 2020 | Beta | October 27, 2005 |

| 25 | Delta | October 5, 2020 | Gamma | November 15, 2005 |

| 26 | Epsilon | October 19, 2020 | Delta | November 22, 2005 |

| 27 | Zeta | October 25, 2020 | Epsilon | November 29, 2005 |

| 28 | Eta | November 1, 2020 | Zeta | December 30, 2005 |

| 29 | Theta | November 10, 2020 | Earliest formation by virtue of being the first of that number | |

| 30 | Iota | November 13, 2020 | ||

| Source:[27] * Record has since been broken. | ||||

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1 and ended on November 30.[9] The season featured 31 tropical depressions,[28] 30 of which became tropical or subtropical storms. The latter total surpassed the previous record of 28 set in 2005.[29] Of the 30 tropical or subtropical storms, 14 of those intensified into hurricanes, which is the second highest number ever observed,[29] behind only 2005.[30] Seven of the hurricanes intensified into major hurricanes, tying 2005 for the most in one season.[31] It was the fifth consecutive Atlantic hurricane season with above average activity, exceeding the previous longest streak of four years between 1998 and 2001. A total of 10 tropical cyclones underwent rapid intensification, tying the record set in 1995.[29]

The season also featured activity at a record pace. The third named storm and each one from the fifth onwards formed on an earlier date in the year than the corresponding storm in any other season since reliable records began in 1851.[27] The ACE index for the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season as calculated by Colorado State University using data from the National Hurricane Center was 179.8 units,[32] reflecting the season's well-above-average activity.[33]

The season marked the extension of the warm phase of the Atlantic multidecadal oscillation, which has been ongoing since 1995. The warm AMO favors active Atlantic hurricane seasons and tropical cyclones which are more intense and often have longer durations. As a result, sea surface temperatures across the Atlantic basin were generally warmer-than-average. A strong west African monsoon, favorable wind patterns from Africa, weaker vertical wind shear all aided in the formation of tropical cyclones. Furthermore, the presence of a La Niña contributed to the unprecedented amount of activity during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season.[34]

Climate change also likely played a role in the record-breaking season. Scientific American noted that "As the oceans absorb more and more of the excess heat trapped by greenhouse gases, waters will get warmer earlier in the season, which could help set new records in the future."[27] A formal attribution study showed that the extreme rainfall was higher than in a counterfactual without climate change, especially for high-intensity storms.[35] Matthew Rosencrans, the lead forecaster at the National Weather Service, emphasized that climate change has been linked to the intensity of storms and their slow movements, but not to the amount of activity, which might instead be increasing due to improvements in technology.[36]

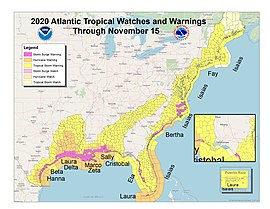

Overall, the Atlantic tropical cyclones of 2020 collectively resulted in 416 deaths and more than $51.114 billion in damage,[37] making the season the fifth costliest on record.[38] A total of eleven named storms made landfall in the United States,[34] breaking the previous record of nine in 1916. Six of these named storms struck the United States at hurricane intensity, tying 1886 and 1985 for the highest number in a single season.[29] Eight of the eleven named storms struck the Gulf Coast of the United States. Outside the United States, a record 13 landfalls occurred.[39] Furthermore, Zeta became the latest major hurricane to strike the United States when it made landfall in Louisiana on October 28, surpassing the previous recordholder, the 1921 Tampa Bay hurricane, by three days.[40]

The United States reported approximately $37 billion in damage from the Atlantic tropical cyclones it was affected by in 2020. Six hurricanes inflicted at least $1 billion in damage in the United States, two more than the previous record of four in 2004 and 2005. Nearly the entire coastline from Texas to Maine was placed under some form of a watch or warning in relation to a tropical system,[29] with only Florida's Jefferson and Wakulla counties being the exception.[41] Only five counties along the East Coast or Gulf Coast of the United States did not experience tropical storm-force winds. Louisiana in particular was heavily impacted in 2020, with the state recording four landfalls – three hurricanes and one tropical storm – tying the record set in 2002.[39]

Central America also experienced devastating impacts during the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season, especially in Honduras and Nicaragua. Both nations were struck by hurricanes Eta and Iota within a few weeks.[29] The former caused at least $6.8 billion in damage in Central America,[42] while the latter caused approximately $1.4 billion in damage in the region, mostly in Honduras and Nicaragua.[3] Eta demolished or damaged more than 6,900 homes and 560 mi (900 km) of bridges and roadways in Nicaragua,[42] though the destruction wrought by the storm would later limit wind damage caused by Iota.[3] In Honduras, both cyclones destroyed tens of thousands of homes and severely impacted more than 4 million people. Furthermore, the Honduras Foreign Debt Forum noted that the two hurricanes set back economic development in Honduras by 22 years.[29]

The season also occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic. Early in the year, officials in the United States expressed concerns the hurricane season could potentially exacerbate the effects of the pandemic for U.S. coastal residents.[43] As expressed in an op-ed of the Journal of the American Medical Association, "there exists an inherent incompatibility between strategies for population protection from hurricane hazards: evacuation and sheltering (i.e., transporting and gathering people together in groups)", and "effective approaches to slow the spread of COVID-19: physical distancing and stay-at-home orders (i.e., separating and keeping people apart)."[44] A study published by GeoHealth in December 2020 confirmed a correlation between destination counties (a county in which an evacuee flees to) and an increase in COVID-19 cases.[45]

Pre/early season activity

[edit]

Tropical cyclogenesis began in the month of May, with tropical storms Arthur and Bertha. This marked the first occurrence of two pre-season tropical storms in the Atlantic since 2016, and the first occurrence of two named storms in the month of May since 2012. For the sixth consecutive year, a tropical cyclone developed in the Atlantic basin prior to the official start of the Atlantic hurricane season,[46] extending the record, which was broken during the previous season.[47] Tropical Storm Cristobal formed on June 1, followed by Tropical Storm Dolly on June 23. Tropical storms Edouard, Fay, and Gonzalo, along with hurricanes Hanna and Isaias, formed in July.[48] Hanna became the first hurricane of the season and made landfall in South Texas,[49] while Isaias became the second hurricane of the season and struck much of the Caribbean and the East Coast of the United States.[50] Tropical Depression Ten also formed in late July off the coast of West Africa but quickly dissipated.[51] July 2020 tied 2005 for the most active July on record in the basin, with five named storms.[52][48]

Peak season activity

[edit]

Tropical storms Josephine and Kyle formed in August, as did hurricanes Laura and Marco.[53] Marco ultimately became the third hurricane of the season, but rapidly weakened and then dissipated near the south central Louisiana coastline.[54] Laura subsequently became the fourth hurricane and first major hurricane of the season. The hurricane later made landfall in southwest Louisiana on August 27 at Category 4 strength with 150 mph (240 km/h) winds.[55] Additionally, a tropical depression formed on the final day of the month which intensified into Tropical Storm Omar on September 1.[56]

September featured the formations of nine named storms: tropical storms Rene, Vicky, Wilfred, and Beta; Subtropical Storm Alpha; and hurricanes Nana (which rapidly formed and was named a few hours ahead of Omar), Paulette, Sally, and Teddy.[57] This swarm of storms coincided with the peak of the hurricane season and the development of La Niña conditions.[58][59] Nana developed on September 1 and made landfall in Belize as a Category 1 hurricane.[60] Paulette struck Bermuda as a Category 2 hurricane, becoming the first tropical or subtropical cyclone to make landfall on that British overseas territory since Gonzalo in 2014.[61] Sally made landfall in Florida just south of Miami as a tropical depression before also striking the Gulf Coast of the United States as a slow-moving Category 2 hurricane and causing extensive damage there.[62]

Teddy, the season's eighth hurricane and second major hurricane formed on September 12,[63] while Vicky formed two days later. With the formation of the latter, five tropical cyclones were simultaneously active in the Atlantic basin for the first time since 1971.[57] Meanwhile, Hurricane Teddy went on to strike Atlantic Canada after transitioning into an extremely large extratropical cyclone on September 23.[63] Additionally, Paulette redeveloped as a tropical storm on September 20 before once again becoming post-tropical two days later.[61] Alpha developed atypically far east in the Atlantic and became the first tropical cyclone on record to strike Portugal.[64] Beta's intensification into a tropical storm made September 2020 the most active month on record, with 10 named storms.[28] Beta went on to make landfall in Texas and impact the Deep South before dissipating,[65] marking an abrupt end to the heavy peak season activity.[27]

Late season activity

[edit]| Rank | Cost | Season |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ≥ $294.803 billion | 2017 |

| 2 | $172.297 billion | 2005 |

| 3 | $120.425 billion | 2022 |

| 4 | ≥ $80.727 billion | 2021 |

| 5 | $72.341 billion | 2012 |

| 6 | $61.148 billion | 2004 |

| 7 | ≥ $51.114 billion | 2020 |

| 8 | ≥ $50.526 billion | 2018 |

| 9 | ≥ $48.855 billion | 2008 |

| 10 | $27.302 billion | 1992 |

October and November were extremely active, with seven named storms developing, five of which intensified into major hurricanes – more than twice the number recorded during this period in any previous season.[66] Hurricane Gamma formed on October 2, before strengthening into the ninth hurricane of the season on October 3. Shortly afterward, Gamma made landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula as a minimal Category 1 hurricane.[67] On the next day, Hurricane Delta developed in the Caribbean south of Jamaica and became the 10th hurricane of the season. Delta explosively intensified into a Category 4 hurricane, before rapidly weakening and making landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula on October 7, as a high-end Category 2 hurricane. It regained Category 3 status in the Gulf of Mexico, before weakening again and making its second landfall in Louisiana on October 9.[68]

After 14 more days of inactivity in the basin, Tropical Storm Epsilon formed in mid-October and became the season's 11th hurricane on October 20.[69] By the following day, Epsilon became a Category 3 hurricane, making it the fourth major hurricane of the season. Afterward, the storm weakened as it slowly moved northward and then northeastward, before becoming extratropical on October 26.[69] During the same month, Hurricane Zeta formed southwest of the Cayman Islands and took a nearly identical track to Delta, striking the Yucatán Peninsula late on October 26, before turning northeastward, accelerating, and making landfall in southeast Louisiana as a Category 3 hurricane, on October 28. Then, after moving rapidly across the eastern United States,[40] its extratropical remnants left behind accumulating snow across parts of New England.[70]

Hurricane Eta, the season's sixth major hurricane, made landfall as a Category 4 storm along the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua on November 3. Eta subsequently moved back into the Caribbean and restrengthened into a tropical storm before taking a winding and erratic path that went over Cuba and through the Florida Keys before stalling in the southern Gulf of Mexico. It then moved north-northeast towards the west coast of Florida, briefly restrengthening into a minimal hurricane along the way.[42] On November 10, Subtropical Storm Theta formed from a non-tropical low over the northeastern Atlantic, before transitioning to a tropical storm later that day.[71] Just after Eta became extratropical off the U.S. East Coast, Hurricane Iota formed over the central Caribbean on November 13, tying 2005 for the most tropical and subtropical cyclones in one year. Iota rapidly intensified into a high-end Category 4 hurricane, becoming the strongest storm of the season, peaking with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (249 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 917 mbar (27.1 inHg).[3] The 2020 season became the first with two major hurricanes in the month of November.[39] Iota then went on to ravage the same areas in Central America that Eta had devastated only two weeks earlier, and dissipated on November 18, over El Salvador.[3]

Systems

[edit]Tropical Storm Arthur

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 16 – May 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 990 mbar (hPa) |

The NHC issued a Special Tropical Weather Outlook on May 15 concerning the potential for tropical or subtropical cyclogenesis from a trough of low pressure located over the Straits of Florida.[72] Tropical Depression One formed from this low around 18:00 UTC on May 16, about 125 mi (200 km) east of Melbourne, Florida. Six hours later, an Air Force reconnaissance aircraft found that it had attained tropical storm strength. Tropical Storm Arthur weaved along the Gulf Stream and changed little in intensity as it encountered increasing wind shear. At 06:00 UTC on May 19, while located about 190 mi (305 km) east-northeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, the storm reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 990 mbar (29 inHg). Shortly thereafter, Arthur interacted with a non-tropical front and became an extratropical cyclone by 12:00 UTC on May 20. The low turned southeast before dissipating near Bermuda a day later.[73]

Tropical Storm Bertha

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 27 – May 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Storm Bertha developed off the northeast coast of Florida on May 27. It intensified to reach a peak of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a central pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg) as it approached land. while located about 35 mi (55 km) east-southeast of Charleston, South Carolina. At 13:30 UTC that same day, Bertha made landfall near Isle of Palms, South Carolina, and quickly weakened into a tropical depression. Early on May 28, it transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over western Virginia, before dissipating over the Northern Panhandle of West Virginia several hours later.[74] In Florida, the precursor of Bertha brought up to 15 in (380 mm) of rainfall and localized flooding to the Miami area.[74][75] One person drowned in South Carolina due to rip currents generated by the storm.[76] Flash flooding affected coastal areas and as far inland as West Virginia.[74][77][78] Overall, Bertha left at least $133,000 in damage.[79][77]

Tropical Storm Cristobal

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 1 – June 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 988 mbar (hPa) |

On June 1, the remnants of Eastern Pacific Tropical Storm Amanda entered the Bay of Campeche, quickly redeveloping into Tropical Depression Three. On the next day, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Cristobal, which strengthened while moving southeastward.[nb 6] The storm made landfall just west of Ciudad del Carmen at 13:35 UTC on June 3 at its peak intensity of 60 mph (95 km/h). Cristobal weakened into a tropical depression over land, but restrengthened as it moved back over the Gulf of Mexico. Cristobal dropped rainfall throughout the Yucatán Peninsula, reaching 9.6 in (243 mm). Three people died in Mexico due to the storm.[80] In El Salvador, a mudslide caused seven people to go missing.[81] Once back over water, Cristobal reattained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) before encountering unfavorable conditions. Late on June 7, the storm moved ashore southeastern Louisiana, and weakened to a tropical depression as it continued northward. Cristobal became an extratropical low on June 10 over Iowa, and lasted two more days before dissipating over the Hudson Bay.[80] Cristobal killed three people in the United States.[80] Overall damage was estimated at US$665 million.[82]

Tropical Storm Dolly

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 22 – June 24 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

Around June 17, an area of disturbed weather developed just north of the Bahamas after part of a tropical wave and an upper-level trough interacted. The disturbance moved north and organized into a low-pressure area early on June 22. Shortly thereafter, the low became a subtropical depression about 405 mi (650 km) east-southeast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Mid-level dry air and sea surface temperatures that were only marginally favorable resulted in very little strengthening on June 22. However, after moving east-northeastward and away from an upper low, the cyclone developed more deep convection and intensified into Subtropical Storm Dolly by 06:00 UTC on June 23. About six hours later, Dolly transitioned into a tropical cyclone and peaked with sustained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,000 mbar (30 inHg). However, convection rapidly diminished after Dolly moved north of the Gulf Stream and encountered drier air. Early on June 24, Dolly degenerated into a remnant low about 200 mi (320 km) south of Sable Island. The remnant low continued northeastward and dissipated south of Newfoundland early the next day.[83]

Tropical Storm Edouard

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 4 – July 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A weak frontal system led to the development of a tropical depression on July 4, located about 290 mi (465 km) west-southwest of Bermuda. The depression passed about 70 mi (110 km) northwest of Bermuda around 08:00 UTC on July 5, producing wind gusts of 43 mph (68 km/h). Moving northeastward, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Edouard on July 6, reaching peak winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg). Soon after, Edouard merged with an approaching frontal system, which continued across the Atlantic Ocean, eventually moving across Ireland and Great Britain. The low dissipated on July 9.[84] Edouard's extratropical remnants brought rainfall to western Europe.[85][86]

Tropical Storm Fay

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 9 – July 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 998 mbar (hPa) |

The same trough that produced Tropical Storm Edouard also produced an area of thunderstorms over the northern Gulf of Mexico on July 5. After moving across the southeastern United States, the system developed into Tropical Storm Fay on July 9 near Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. Moving northward, the storm reached peak winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 998 mbar (29. 47 inHg) late on July 10. At 20:00 UTC that day, Fay made landfall near Atlantic City, New Jersey, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). It quickly lost intensity inland, degenerating into a remnant low while over southeastern New York and later being absorbed into a larger mid-latitude low over southeastern Canada.[87]

Fay directly caused the deaths of two people, who drowned due to rip currents; four others drowned due to the residual high surf conditions after Fay had passed by.[87] Overall, damage from the storm in the Northeastern United States totaled at least $350 million.[82] New Jersey experienced some of the worst impacts from Fay. Heavy rainfall caused flooding in several Jersey Shore towns and resulted in closures along many roadways, including the New Jersey Turnpike.[88] Wind gusts up to 54 mph (87 km/h) left at least 10,000 people in the state without electricity.[87][89]

Tropical Storm Gonzalo

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 21 – July 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

A dry, thermal low-pressure area merged with a tropical wave just offshore the west coast of Africa on July 15. Scatterometer data early on July 21 indicated that a small, but well-defined low-pressure area formed well east of the Lesser Antilles. After a steady increase in deep convection, the low developed into a tropical depression around 18:00 UTC about 1,440 mi (2,315 km) east of the Windward Islands. Light wind shear and sea surface temperatures of 82 °F (28 °C) allowed the depression to intensify into Tropical Storm Gonzalo around 06:00 UTC on July 22. Gonzalo moved generally westward due to the Bermuda-Azores high-pressure. Gonzalo soon reached peak intensity, with sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 997 mbar (29.4 inHg) at 06:00 UTC on July 23, as very dry air from Saharan Air Layer to its north significantly disrupted the central dense overcast. The storm then encountered high wind shear, causing the cyclone to weaken. It weakened to a tropical depression before landfall on Trinidad just north of Manzanilla Beach. Likely due to land interaction, Gonzalo weakened further and degenerated into an open trough near Venezuela's Paria Peninsula by 00:00 UTC on July 26.[90]

On July 23, hurricane watches were issued for Barbados and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, but were replaced with tropical storm warnings. The storm brought squally weather to Trinidad and Tobago and parts of southern Grenada.[90] However, the storm's impact ended up being significantly smaller than originally anticipated.[91] Only two reports of wind damage were received: a fallen tree on a health facility in Les Coteaux and a damaged bus stop roof in Argyle.[90]

Hurricane Hanna

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 23 – July 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved through Florida into the Gulf of Mexico, leading to the formation of a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on July 23 about 235 mi (380 km) south-southeast of Louisiana. Moving to the west-northwest, the depression soon intensified into Tropical Storm Hanna, developing an eye. Hanna reached hurricane status on July 25, reaching peak winds of 90 mph (140 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 973 mbar (28.7 inHg) before making landfall on Padre Island, Texas, and later the Kenedy County mainland. The system rapidly weakened after moving inland, dropping to tropical depression status at 18:00 UTC on July 26 near Monterrey, Nuevo León, and then dissipating shortly thereafter.[49]

In Walton County, Florida, a 33-year-old man drowned in rip currents while rescuing his son.[49] Hanna brought storm surge flooding, destructive winds, torrential rainfall, flash flooding across South Texas. The storm destroyed several mobile homes, deroofed many poorly-built structures, and left around 200,000 homes in Cameron and Hidalgo counties combined without power. In the United States, Hanna caused about $1.1 billion in damage. In Mexico, heavy rain fell in Coahuila, Nuevo León, and Tamaulipas. The cyclone directly caused four deaths in Mexico and caused approximately $100 million in damage.[49]

Hurricane Isaias

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 30 – August 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved across the Atlantic toward the end of July, leading to the development of Tropical Storm Isaias on July 30 in the eastern Caribbean Sea. Moving northwestward, Isaias struck the Dominican Republic and later the Bahamas as it intensified into a hurricane. Curving to the north, Isaias weakened to tropical storm status, but re-intensified back into a hurricane on August 3. At 03:10 UTC the next day, Isaias made landfall in Ocean Isle Beach, North Carolina, with sustained winds of 90 mph (140 km/h). It soon weakened into a tropical storm as it passed over the Mid-Atlantic states, before transitioning to an extratropical low around 00:00 UTC on August 5 while situated over central Vermont, and dissipating several hours later over Quebec.[50]

Isaias caused 17 deaths across the Greater Antilles and eastern United States: 14 in the continental United States, 2 in the Dominican Republic, and 1 in Puerto Rico. Damage estimates exceeded $4.8 billion. Isaias caused devastating flooding and wind damage in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. In the United States, Isaias produced an outbreak of 39 tornadoes, including an EF3 tornado in North Carolina that killed two people. Strong winds, storm surge, and many tornadoes left significant damage in the Northeastern United States. Almost 3 million people were without electricity at the height of the storm.[50]

Tropical Depression Ten

[edit]| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 1 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

On July 28, a tropical wave emerged off the west coast of Africa. The system soon developed a defined low pressure center on July 29 as it turned north along the east side of an upper-level low. Associated convection became sufficiently organized for the system to be classified as a tropical depression the following day; at this time the cyclone was located about 230 mi (370 km) east-southeast of the easternmost Cabo Verde Islands. The system reached its peak intensity with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a pressure of 1008 mbar (29.77 inHg) around 00:00 UTC on August 1. Scatterometer data revealed conflicting data, with tropical storm-force winds noted in one pass within the deepest convection to the southwest of the storm's center where the weakest winds are typically found. A near-concurrent pass from another satellite showed lower winds and the highest winds were determined to be rain-inflated, and given the conflicting data the NHC determined the system to have not become a tropical storm. Thereafter, a combination of decreasing sea surface temperatures and dry air caused convection to dissipate. The depression turned west-northwest and degraded into a remnant low later that day. It soon dissipated on August 2 north of the Cabo Verde Islands.[51]

Tropical Storm Josephine

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On August 7, the NHC began monitoring a tropical wave over the tropical Atlantic. Shower and thunderstorm activity on the wave axis increased as it moved westward at 17–23 mph (27–37 km/h) and a mid-level circulation formed on August 9, although the low-level circulation remained elongated and poorly-organized. The wave's circulation then became defined and a low-pressure system with disorganized convection formed late on August 10. A burst of convection near the center followed by some subsequent organization allowed the system to be designated Tropical Depression Eleven at 06:00 UTC on August 11 about 920 mi (1,480 km) west-southwest of the Cabo Verde Islands. However, the depression's ability to intensify was initially hindered by dry mid-level air and moderate easterly wind shear. After over two days with little change in intensity, the shear relaxed some, allowing convection to begin to form closer to the estimated center of the depression. This allowed it to strengthen into Tropical Storm Josephine at 12:00 UTC on August 13, reaching an initial peak intensity of 45 mph (70 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,005 mbar (29.7 inHg).[92]

Josephine's intensity began to fluctuate on August 14, as wind-shear affected the system, causing convection to be displaced from the circulation. Hurricane hunter aircraft investigated the system later that day and found that the storm's center had relocated further north in the afternoon hours and Josephine reached its peak intensity with winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,004 mbar (29.6 inHg) at 18:00 UTC. Nonetheless, Josephine headed into increasingly hostile conditions as it began to pass north of the Leeward Islands. As a result, the storm later weakened, becoming a tropical depression at 06:00 UTC on August 16, just north of the Virgin Islands. The weakening cyclone's circulation became increasingly ill-defined, and Josephine eventually weakened into a trough of low pressure 12 hours later.[92]

Tropical Storm Kyle

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 14 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

A mesoscale convective system moved offshore of South Carolina and Georgia early on August 11. The convective activity weakened that day, but a small mid-level circulation formed from the system and it re-developed some thunderstorm activity that night while it moved slowly northeastward off the coast of South Carolina. This activity generated the development of a weak low-level circulation that moved near the coast of southern North Carolina late on August 12. The system became better organized the next day, although it lacked a well-defined center and banding features. The low then moved offshore of the Outer Banks early on August 14,[93] and deep convection increased as most of the circulation was over the warm water temperatures in the Atlantic.[94] The low became better defined overnight as a result of the convection, and became Tropical Storm Kyle around 12:00 UTC on August 14, about 105 mi (170 km) east-northeast of Duck, North Carolina. The storm then moved quickly east-northeastward along the Gulf Stream due to the flow between a broad mid-level trough over the Northeastern United States and the western Atlantic subtropical ridge. Despite moderate-to-strong wind shear, Kyle strengthened on August 15, reaching its peak intensity around 12:00 UTC with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum pressure at 1,000 mbar (30 inHg) about 230 mi (370 km) southeast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The storm began to weaken afterward due to increasing shear and interaction with a stationary front; its circulation began to become elongated as a result. Kyle became an extratropical cyclone when it embedded itself within the front at 00:00 UTC August 16. Its center dissipated and the remnants were absorbed into the front shortly thereafter.[93] Several days later, extratropical European windstorm Ellen, which contained remnants of Tropical Storm Kyle, brought hurricane-force winds to the Republic of Ireland and the United Kingdom.[95][96]

Hurricane Laura

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 20 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 937 mbar (hPa) |

On August 16, a tropical wave exited Africa and moved across the Atlantic. Four days later, Tropical Depression Thirteen developed about 980 mi (1,580 km) east-southeast of Antigua, which quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Laura. Wind shear prohibited further intensification as the storm moved across the northern Leeward Islands, the Dominican Republic, and later Cuba. Laura entered the Gulf of Mexico later on August 25, where it became a hurricane around 12:00 UTC that day. Laura then began a period of rapid intensification, and over a 24-hour period ending at 00:00 UTC on August 27, it intensified by about 65 mph (105 km/h), to Category 4 strength. At that time, Laura reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and minimum pressure 937 mbar (27.7 inHg) while located less than 90 mi (140 km) south of Creole, Louisiana. Laura's pressure then rose slightly to 939 mbar (27.7 inHg), but the storm maintained its peak winds as it made its final landfall near Cameron, Louisiana, at 06:00 UTC.[55] The hurricane became the strongest Louisiana-landfalling tropical cyclone in terms of wind speed since the 1856 Last Island hurricane.[97] Laura weakened over land, dropping to tropical depression status over Arkansas by August 28. The deteriorating system turned northeastward and degenerated into a remnant low over northern Kentucky on August 29, which was soon absorbed by another low near the Great Lakes region.[55]

As Laura passed through the Northern Leeward Islands, it brought heavy rainfall to Guadeloupe and Dominica,[98] and prompted the closing of all ports in the British Virgin Islands.[99] The storm produced heavy downpours upon Puerto Rico and Hispaniola.[100] The storm left extensive damage in Louisiana, especially in the southwest region of the state. Storm surge penetrated up to nearly 35 mi (55 km) inland, while Creole and Grand Chenier were inundated with coastal floodwaters ranging from 12 to 18 ft (3.7 to 5.5 m) above ground, sweeping away structures in Cameron Parish. Wind gusts reached up to 153 mph (246 km/h) at Holly Beach, resulting in catastrophic wind damage in Calcasieu and Cameron parishes. Outside of the two parishes, Beauregard and Vernon parishes were next hardest hit, with the core of the storm passing directly over. Several other parishes reported damage to homes and buildings due to strong winds or falling trees.[55] Laura destroyed approximately 10,000 homes and damaged over 130,000 others in the state.[101] Damage in Louisiana alone totaled about $17.5 billion. Texas was second hardest hit by the storm, with high winds downing many power lines, power poles, and trees in the eastern part of the state, while some counties reported damage to businesses and homes. Laura produced 16 tornadoes in the United States, the most significant of them being an EF2 tornado in Randolph County, Arkansas. Altogether, there were 81 storm related deaths. Of these, 47 were direct deaths associated with Laura, including 31 in Haiti, 9 in the Dominican Republic, and 7 in the United States. There were also 34 indirect deaths, all of them in the United States.[55]

Hurricane Marco

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 21 – August 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 991 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Fourteen developed on August 21 from a tropical wave near the coasts of Nicaragua and Honduras. The system moved northwestward and intensified, becoming Tropical Storm Marco around 00:00 UTC on August 22, as it moved over the northwestern Caribbean. The storm strengthened further as it moved through the Yucatán Channel.[54] Rainfall in western Cuba reached 5.72 in (145 mm) at Cape San Antonio, causing flash flooding.[54][102] Marco became a hurricane on August 23 in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico, with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 991 mbar (29.3 inHg). Stronger wind shear caused Marco to weaken to a tropical storm on August 24 as it was approaching the coast of Louisiana. The storm turned westward and avoided moving ashore, degenerating into a remnant low on August 25 without making landfall.[54] Heavy rains fell along parts of the Gulf Coast of the United States between Florida and Mississippi, with up to 13.17 in (335 mm) of precipitation near Apalachicola, Florida.[54] Floodwaters inundated many streets in Panama City Beach.[103] Overall, Marco left approximately $35 million in damage throughout its path.[104]

Tropical Storm Omar

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 31 – September 5 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous mid to upper-level shortwave trough moved into the Southeastern United States on August 29. The shortwave trough then interacted with the remnants of a frontal system, resulting in the formation of a low-pressure area offshore northeast Florida on August 30. Drifting over the Gulf Stream, the low quickly organized into a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on August 31 while situated about 150 mi (240 km) south-southeast of Wilmington, North Carolina. Dry air and vertical wind shear offset the warm sea surface temperatures as the system headed northeastward. However, following a burst in deep convection, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Omar around 12:00 UTC on September 1. The storm then peaked with sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1003 mbar (29.6 inHg). An increase in wind shear kept Omar weak. Consequently, the storm struggled to maintain deep convection as it moved eastward and weakened to a tropical depression early on September 3. Omar decelerated due to a weak steering flow, turning northward on September 5, due to a southerly flow associated with a deep-layer trough. Although the cyclone experienced periodic bursts of convection, strong wind shear eventually caused the storm to degenerate into a remnant low about 575 mi (925 km) northeast of Bermuda late on September 5. The low moved generally northward before being absorbed by a frontal system on the following day.[56]

Hurricane Nana

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

Toward the end of August, a tropical wave moved through the Caribbean Sea, with a concentrated area of convection. On September 1, Tropical Storm Nana developed about 180 mi (290 km) southeast of Kingston, Jamaica. Despite the presence of wind shear, the storm was able to intensify, becoming a hurricane early on September 3 near the coast of Belize. At that time, Nana had maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 994 mbar (29.4 inHg). Soon after, the hurricane made landfall about 50 mi (80 km) south of Belize City, and it rapidly weakened over land, dissipating on September 4.[60] The hurricane caused more than US$20 million in damage in Belize.[105] The winds destroyed crops and caused coastal flooding.[60][106] Heavy amounts of precipitation also occurred in northern Guatemala and southeastern Mexico. The remnants later regenerated into Tropical Storm Julio in the eastern Pacific on September 5.[60]

Hurricane Paulette

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression Seventeen developed on September 7 from a tropical wave, roughly 1,150 mi (1,850 km) west of the Cabo Verde Islands. Moving west-northwestward, it quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Paulette. Wind shear impeded the storm's development, but Paulette was able to strengthen into a hurricane early on September 13, about 415 mi (670 km) southeast of Bermuda. It turned northward and made landfall on Bermuda at 08:50 UTC on September 14 with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The storm reached its peak intensity later that day, with maximum sustained winds of 105 mph (169 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg). Paulette accelerated northeastward and weakened, becoming an extratropical cyclone on September 16 to the southeast of Newfoundland. After gradually weakening over the following few days and slowly curving southward, the extratropical cyclone started regenerating convection, and Paulette became a tropical storm again on September 20 about 230 mi (370 km) south-southwest of the Azores. After reaching a secondary peak of 60 mph (95 km/h), Paulette became post-tropical on September 23, which continued to meander for several days without redevelopment. The low degenerated into a trough late on September 28.[61]

Paulette caused two fatalities and one injury, due to rip currents along the east coast of the United States. Paulette produced hurricane-force winds on Bermuda, with sustained winds reaching 79 mph (127 km/h) at Pearl Island and surface-level gusts reaching 97 mph (156 km/h) at L.F. Wade International Airport. The hurricane led to 25,000 power outages, or about 70 percent of electrical customers on the island. Damage on Bermuda totaled approximately $50 million.[61]

Tropical Storm Rene

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 7 – September 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa on September 6, leading to the formation of Tropical Depression Eighteen on September 7 about 200 mi (320 km) east of Cabo Verde. It soon strengthened into Tropical Storm Rene, which hit Boa Vista Island around 00:00 UTC on September 8 with sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h).[107] The storm brought gusty winds and heavy rains to Cabo Verde.[108] Rene weakened to a tropical depression several hours, but re-strengthened into a tropical storm early on September 9. At 12:00 UTC on September 10, Rene peaked with sustained winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg). Dry air caused thunderstorms to diminish, and Rene weakened to a tropical depression on September 12. Strong westerly shear caused further weakening, with Rene degenerating into a trough on September 14 about 1,035 mi (1,665 km) northeast of the Leeward Islands. The remnants turned southwestward and dissipated a few days later.[107]

Hurricane Sally

[edit]| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 11 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min); 965 mbar (hPa) |

In early September, a trough developed over the western Atlantic, leading to the formation of Tropical Depression Nineteen on September 11 over the Bahamas. Moving westward, the depression made landfall near Cutler Bay, Florida early on September 12. While moving over the Everglades, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Sally, which soon emerged into the Gulf of Mexico. Sally moved northwestward, intensifying into a hurricane on September 14. The hurricane slowed to a crawl while turning north-northeastward, becoming a high-end Category 2 hurricane by 06:00 UTC September 16. At around 09:45 UTC that day, the system made landfall at peak intensity near Gulf Shores, Alabama, with maximum sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h) and a minimum central pressure of 965 mbar (28.5 inHg). Sally quickly weakened over land, becoming an extratropical low on September 17, which was later absorbed within a cold front.[62]

Across the United States, Sally was responsible for nine fatalities and approximately $7.3 billion in damage. The storm caused widespread power outages affecting at least 560,000 people. In its early stages, Sally dropped heavy rainfall in South Florida, causing flooding. The hurricane destroyed approximately 50 structures in the Florida Panhandle, while thousands of others in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties suffered damage. There were 23 tornadoes reported across the Southeastern United States while Sally was a tropical cyclone.[62]

Hurricane Teddy

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 23 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 945 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged from the west coast of Africa on September 10, leading to the formation of a tropical depression two days later. On September 14 it intensified into Tropical Storm Teddy, which continued to strengthen while moving across the Atlantic Ocean. Teddy became a hurricane on September 16, and two days later it reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 945 mbar (27.9 inHg). Teddy weakened due to an eyewall replacement cycle and increased wind shear. The cyclone passed about 230 mi (370 km) east of Bermuda on September 21 as it turned north-northeastward. Teddy interacted with an approaching trough, causing the hurricane to re-intensify and become more asymmetric. The hurricane became an extratropical cyclone on September 23, and soon after moved ashore Atlantic Canada near Ecum Secum, Nova Scotia, with sustained winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). The system was eventually absorbed by a larger non-tropical low early on September 24 near eastern Labrador.[63]

Hurricane Teddy generated large ocean swells which spread along much of the U.S. Atlantic coast and from the northern Caribbean to Bermuda, killing three people. Abnormally high tides also caused coastal flooding in Charleston, South Carolina, and the Outer Banks of North Carolina. About 220 households lost power in Bermuda. The extratropical remnants of Teddy generated wind gusts up to 90 mph (145 km/h) in Nova Scotia. Approximately 18,000 customers throughout the Atlantic Canada region lost electricity. There were also isolated reports of minor flooding.[63] Damage from Teddy in all areas impacted totaled roughly $35 million.[104]

Tropical Storm Vicky

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 14 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

In the early hours of September 11, a tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa. An area of low pressure associated with the wave moved northwestward and crossed the Cabo Verde Islands on September 12, producing showers and locally heavy rain. The next day, the disturbance steadily organized, and by 00:00 UTC on September 14, the system became Tropical Depression Twenty-One about 195 mi (315 km) west of the northwesternmost of the Cabo Verde Islands. The depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Vicky six hours later based on scatterometer data. Despite extremely strong shear partially caused by Hurricane Teddy's outflow removing all but a small convective cluster to the northeast of its center, Vicky intensified further, reaching its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a pressure of 1,001 mbar (29.6 inHg) at 12:00 UTC on September 15. Over the ensuing couple of days, the storm was beset by increasing wind shear, and it weakened to a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC on September 17. Then, about six hours later, it degenerated into a remnant low about 920 mi (1,480 km) west-northwest of the northwesternmost Cabo Verde Islands and subsequently dissipated.[109]

The precursor tropical wave of Vicky produced flooding in the Cabo Verde Islands.[109] Within a 24-hour period, approximately 5 in (88 mm) of precipitation fell in the capital city of Praia. Flooding blocked several roads and damaged automobiles, bridges, buildings, and farmland.[110] The floods killed one person in Praia on September 12.[109]

Tropical Storm Wilfred

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave and its associated broad low-pressure area emerged into the Atlantic from the west coast of Africa on September 13. A well-defined center of circulation formed on September 17 as the result of a strong burst of deep convection formed near the center of the low. Stronger and more organized convection appeared later that day, while a scatterometer pass revealed that the circulation had become better defined, and the presence of tropical-storm-force winds. As a result, Tropical Storm Wilfred developed around 18:00 UTC on September 17 while situated about 345 mi (555 km) southwest of the southernmost islands of Cabo Verde. Six hours later, the storm attained its peak intensity with sustained winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 1,006 mbar (29.7 inHg). Very dry air from the Saharan Air Layer prevented further intensification, while westerly to northwesterly wind shear increased to about 23 mph (37 km/h) by September 19. Deep convection began to diminish on the following day, causing Wilfred to weaken to a tropical depression around 12:00 UTC. Early on September 21, Wilfred degenerated into an open trough approximately 920 mi (1,480 km) east of the northern Leeward Islands.[111]

Subtropical Storm Alpha

[edit]| Subtropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 19 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 996 mbar (hPa) |

A large extratropical low developed over the northeast Atlantic Ocean on September 14, which moved south-southeastward. The wind field contracted as thunderstorms formed over the circulation. On September 17, the system developed into Subtropical Storm Alpha roughly 405 mi (650 km) east of the Azores. Alpha strengthened to attain winds of 50 mph (80 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 996 mbar (29.4 inHg). At 18:40 UTC on September 18, the cyclone made landfall about 10 mi (15 km) south of Figueira da Foz, Portugal. It dissipated by the next day.[64] Alpha caused more than $1 million in damage,[105] and resulted in one fatality due to a collapsed roof in Calzadilla, Spain.[64] The storm also spawned at least two tornadoes, both rated EF1 on the Enhanced Fujita scale. In Spain, the front associated with Alpha caused a train to derail in Madrid,[64] while thunderstorms on Ons Island caused a forest fire.[112]

Tropical Storm Beta

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 17 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 993 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather was first observed on September 5, stretching from the western Caribbean to offshore the Southeastern United States. The influence of nearby Hurricane Sally initially prevented further development. A day after that hurricane moved ashore, Tropical Depression Twenty-Two developed in the Gulf of Mexico on September 17, located about 350 mi (565 km) south-southeast of Brownsville, Texas. On September 18, the depression became Tropical Storm Beta, reaching peak winds of 65 mph (105 km/h) two days later. The storm slowed its movement,[65] resulting in upwelling, which caused weakening.[113] Beta made landfall early on September 22 near Port O'Connor, Texas, soon weakening and becoming extratropical. The low dissipated over northeastern Alabama early on September 25.[65] The storm dropped heavy rainfall, with a total of 15.77 in (401 mm) in Brookside Village, Texas. The rains led to flooding across the Greater Houston metropolitan area, resulting in a drowning death in Brays Bayou. Throughout the United States, Beta caused approximately $225 million in damage.[65] Rising floodwaters necessitated more than 100 high-water rescues and the closures of several highways and interstates in the area.[114][115]

Hurricane Gamma

[edit]| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 2 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 978 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed on October 2 in the northwestern Caribbean Sea, about 300 mi (485 km) southeast of the Yucatán peninsula. It quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Gamma and intensified further into a hurricane, reaching winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 978 mbar (28.9 inHg) as it made landfall near Tulum, Quintana Roo on October 3. Gamma weakened over land and emerged into the southern Gulf of Mexico, encountering wind shear and dry air. It weakened into a tropical depression before making another landfall on the Yucatán peninsula on October 6, near San Felipe, Yucatán. Soon after, Gamma was absorbed by approaching Hurricane Delta.[67] Hurricane Gamma caused at least six deaths in Mexico, while damage was estimated at $100 million.[67][104] Precipitation peaked at 15.11 in (384 mm) in Tizimin.[67] The storm produced strong winds, heavy rainfall, flash flooding, landslides, and mudslides in the region.[116] Gamma's outerbands also produced heavy rainfall in the Cayman Islands, Cuba, and Florida.[117]

Hurricane Delta

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 4 – October 10 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 953 mbar (hPa) |

In early October, a tropical wave moved across the Caribbean, leading to the formation of Tropical Depression Twenty-Six on October 4 to the southeast of Jamaica. It intensified into Tropical Storm Delta, and soon began a period of rapid intensification, as convection became more symmetrical. Delta became a hurricane at 00:00 October 6, and later that day peaked as a Category 4 hurricane with maximum winds of 140 mph (230 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 953 mbar (28.1 inHg). This period of rapid intensification resulted in a 105 mph (170 km/h) increase in winds over a 36-hour period, caused by a combination of extremely warm ocean water temperatures, low wind shear, and sufficient moisture. However, an increase in wind shear caused Delta to weaken, and on October 7 the hurricane struck the eastern Mexican state of Quintana Roo as a Category 2 hurricane with sustained winds of 105 mph (170 km/h). Delta weakened over land, but re-intensified over the Gulf of Mexico, reaching a secondary peak of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 953 mbar (28.1 inHg) on October 9. Later that day, unfavorable conditions caused the hurricane to weaken, and Delta made its final landfall near Creole, Louisiana with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h). The landfall was about 10 mi (15 km) east of where Hurricane Laura's eye crossed the coast on August 27. Inland, Delta weakened to tropical storm, and later became extratropical over Mississippi late on October 10. The system degenerated into a trough over Tennessee two days later.[68]

Hurricane Delta caused six fatalities, two each in the Yucatán, Louisiana, and Florida. In Mexico, damage in Mexico totaled approximately $185 million, with power outages, uprooted trees, and flooding. Damage from Delta in the United States reached $2.9 billion. The hurricane and its remnants produced heavy rain, strong winds, storm surge, and tornadoes across much of the Southeastern United States. In Louisiana, strong winds generated by Delta caused additional damage to structures that were impacted by Laura, while debris remaining from Hurricane Laura were scattered across roadways and drains. However, much of the damage in the state was caused by flooding, with 17.57 in (446 mm) of rainfall at LeBleu Settlement. Floodwaters entered several homes in Baton Rouge and Calcasieu. In Mississippi, roughly 100,000 businesses and homes lost electricity after rainfall and tropical storm-force wind gusts uprooted trees.[68]

Hurricane Epsilon

[edit]| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 19 – October 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 952 mbar (hPa) |

A non-tropical low formed on October 16 to the east of Bermuda. Moving southward over warmer waters, the system developed enough organized convection to become Tropical Depression Twenty-Seven on October 19. It soon intensified into Tropical Storm Epsilon as it executed a small counter-clockwise loop. Dry air and wind shear affected the storm at first, but Epsilon strengthened once the shear subsided and it began a northwest track. The storm became a hurricane on October 21, and a day later Epsilon reached maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 952 mbar (28.1 inHg). Epsilon marked the farthest east that a major hurricane had been observed after October 20. It soon weakened, passing about 185 mi (300 km) to the east of Bermuda as a minimal hurricane on October 23. After turning to the northeast, Epsilon weakened to a tropical storm, becoming an extratropical storm on October 26 about 565 mi (910 km) east of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[69] Epsilon's remnants were later absorbed into a deep extratropical low southwest of Iceland.[118]

The hurricane caused one direct death; a 27-year-old man drowned in Epsilon-induced rip currents in Daytona Beach, Florida. The hurricane also generated large sea swells from Bermuda to the Bahamas, the Greater Antilles, and the Leeward Islands. Rainfall on the island as the storm passed by amounted to less than 1 in (25 mm); winds at Bermuda's airport gusted near tropical storm-force, with a peak wind gust of 38 mph (61 km/h).[69] The trailing weather fronts associated with this low produced waves up to 98 ft (30 m) on the coast of Ireland on October 28.[119]

Hurricane Zeta

[edit]| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 24 – October 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

The interaction of a tropical wave and a midlevel trough led to the formation of Tropical Depression Twenty-Eight on October 24 near Grand Cayman. It quickly intensified into Tropical Storm Zeta, and reached hurricane status on October 26. That day, Zeta made landfall near Ciudad Chemuyil, Quintana Roo, with winds of 85 mph (135 km/h). After weakening to a tropical storm inland, Zeta moved offshore of the northern coast of the Yucatán Peninsula about 11 hours later. On October 28, it reattained hurricane status as it turned northward. Zeta peaked later that day at 21:00 UTC when it became a Category 3 major hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 970 mbar (29 inHg), as it made its second landfall near Cocodrie, Louisiana. Zeta steadily lost strength after landfall, weakening to a tropical storm over Alabama at 06:00 UTC on October 29, before transitioning into a post-tropical cyclone over central Virginia by 18:00 UTC that day, while moving rapidly northeastward. Early on October 30, Zeta's remnants dissipated east of the mid-Atlantic U.S. coast.[40]

Heavy rain in Jamaica caused a landslide that killed two people after demolishing a home in Saint Andrew Parish. Zeta left roughly $15 million in damage on the island.[40] Strong winds and rain caused flooding and damaged infrastructure in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.[120] There were seven related deaths in the United States: three in Georgia; two in Mississippi; and one each in Louisiana and Mississippi. Damage within the United States totaled $4.4 billion.[40] Zeta knocked out power to more than 2.6 million homes and businesses across the Southeastern United States; it also disrupted 2020 election early voting in several states.[121] In Louisiana, the cyclone produced hurricane-force winds, with the highest reported sustained wind speed being 94 mph (151 km/h) at Golden Meadow, while the same location recorded gusts up to 110 mph (180 km/h). Zeta had damaging effects as far northeast as Virginia.[40] As the remnants of Zeta moved off shore from the continental U.S., it left behind accumulating snow across parts of New England.[70]

Hurricane Eta

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 31 – November 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 922 mbar (hPa) |

Toward the end of October, a tropical wave moved across the Caribbean Sea, leading to the formation of Tropical Depression Twenty-Nine late on October 31. Moving westward, it strengthened into Tropical Storm Eta and continued to intensify rapidly as it approached Central America. Late on November 2, Eta reached peak intensity with sustained maximum winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 922 mbar (27.2 inHg) at 06:00 UTC on November 3. Later that day, at 21:00 UTC, it made landfall south-southwest of Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, with winds of 140 mph (225 km/h). Over land, Eta rapidly weakened to a tropical depression and lost its surface circulation, although its mid-level center remained present. On November 6, the system redeveloped into a tropical depression, which again became a tropical storm as it moved to the northeast. Eta struck eastern Cuba as it curved back to the northwest, moving across the Florida Keys into the Gulf of Mexico on November 9. The storm briefly re-strengthened into a hurricane southwest of Florida on November 11, before weakening back to tropical storm strength. It then turned northeastward and made its final landfall near Cedar Key, Florida, at 09:00 UTC on November 12, with winds of 50 mph (80 km/h). The storm weakened over land and emerged over the Atlantic Ocean, becoming extratropical on November 13.[42]

Overall, more than 210 fatalities across Central America were attributed to the storm,[122] including 74 in Honduras, 60 in Guatemala, 27 in Mexico,[42] 19 in Panama,[123] 10 in the United States, two each in Nicaragua and Costa Rica,[42] and one in El Salvador.[124] Damage in Central America reached approximately $6.8 billion. The intense wind and rain generated by Eta caused flooding and landslides, resulting in crop losses, plus the destruction of roads, bridges, power lines and houses throughout Central America. The storm damaged or demolished at least 6,900 homes, 45 schools, 16 healthcare facilities, and some 560 mi (900 km) of bridges and roadways throughout Nicaragua. Eta also damaged hundreds of dwellings to some degree in both Guatemala and Honduras. Washed-out bridges and roads isolated more than 40 communities in the latter. In Guatemala, flooding also ruined more than 290,000 acres (119,000 ha) of crops.[42] Mexico suffered significant impacts as well, with thousands of homes damaged in Chiapas and Tabasco.[42] Relief efforts were severely hampered when, just two weeks later, Hurricane Iota made landfall approximately 15 miles (24 km) south of where Eta moved ashore.[125] Eta bought heavy rainfall and gusty winds to the Cayman Islands and Cuba, the latter of which was already dealing with overflowing rivers that prompted the evacuations of 25,000 people. The storm caused roughly $1.5 billion in damage in the United States, mostly related to flooding.[42]

Tropical Storm Theta

[edit]| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 10 – November 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 987 mbar (hPa) |

On November 6, the NHC began monitoring a non-tropical area of disturbed weather in the central Atlantic for possible gradual subtropical development.[126] A non-tropical low subsequently formed about 1,300 mi (2,100 km) west-southwest of the Azores on November 8. The system became better organized as it began to detach from a frontal boundary during the following day. At 00:00 UTC on November 10, it developed into Subtropical Storm Theta. By 18:00 UTC that afternoon, the storm had transitioned into a tropical storm; it simultaneously attained what would be its peak intensity, with maximum winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 987 mbar (29.1 inHg). By the following morning, the effects of strong southwesterly shear had weakened Theta somewhat, though it soon began to regain some strength, and by 00:00 UTC on November 12, re-intensified to its earlier peak. Steady weakening occurred on November 13–14, as the storm experienced strong northerly vertical shear. By 06:00 UTC on November 15, Theta had weakened to a tropical depression about 120 mi (195 km) southwest of Madeira Island, and it degenerated to a remnant low six hours later.[71]

Hurricane Iota

[edit]| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 13 – November 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 155 mph (250 km/h) (1-min); 917 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on October 30, which eventually led to the formation of Tropical Depression Thirty-one on November 13. The depression intensified into Tropical Storm Iota as it moved westward through an area of warm waters and low wind shear. Iota rapidly intensified, becoming a hurricane on November 15, and reaching its peak intensity a day later with maximum winds of 155 mph (250 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 917 mbar (27.1 inHg), while located just 23 mi (37 km) northwest of Providencia Island. The hurricane weakened slightly before making landfall at 03:40 UTC on November 17 in eastern Nicaragua with sustained winds of 145 mph (235 km/h). Iota rapidly weakened over land, dissipating late on November 18 over El Salvador.[3] Its landfall location was approximately 15 mi (25 km) south of where Eta made landfall on November 3.[127]